Hashem is the Matchmaker

The Steipler was once asked, "Is it true that if one meets up with many obstacles in the course of a shidduch, this means it was not destined?"

And he replied, "A match need not appear to be one hundred percent perfect in order to be sealed. Sometimes, not all goes smoothly, yet the match turns out for the best, while shidduchim that appear to be good do not always work out, either."

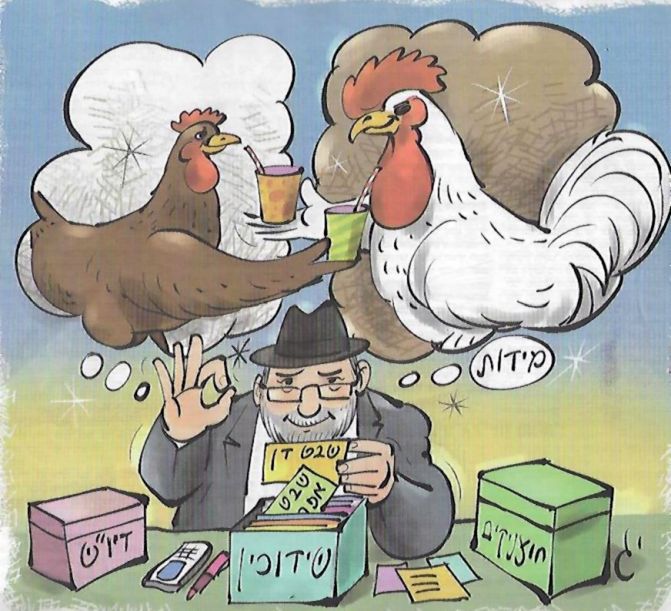

Hashem is the matchmaker, but how does one finally decide upon his match? Each shidduch is accompanied by doubts, hesitations and impediments. As our Sages said: "A person's match is as difficult as the splitting of the sea."

Even though a person may encounter many hardships and doubts along the way, this is no proof that any given match is not the proper one. Who says that it had to be smooth, to begin with? On the contrary, we are explicitly told that it is as difficult as the splitting of the sea!

In the final analysis, a person must seek a girl who is instilled with yiras shomayim, one who will be satisfied with her lot and will wish that her husband continue to study Torah after their marriage." (Karaina DeIgarta).

Famous Shidduchim

How did Hashem bring about the marriage of the daughter of the [Ashkenazi] RaSHaSH and the son of a tailor?

A fascinating story is brought in She'al Ovicha Veyagedcha about how Hashem brought about the marriage of the daughter of the renowned R' Shmuel Strashun, the RaSHaSH whose commentary is at the end of each volume of the Vilna Shas, to the son of a simple tailor.

R' Sholom Schwadron, the famous Jerusalem maggid, told the tale as follows:

The RaSHaSH's son-in-law was actually a very simple fellow. Could the renowned talmid chochom not have had the pick of yeshiva bochurim for his daughter?

Was it that he could not afford an accomplished scholar? Not at all; R' Shmuel was known to be very wealthy and very generous in giving charity. He even established a free loan fund which he managed himself, sometimes lending out large sums.

How, then, did he come to have an unlearned youth for a son-in-law? It was destined to be, but it had to come about in a most complicated manner.

This incredible story was told to me by my own father-in-law. He heard it from a different person who said that he was personally acquainted with the RaSHaSH son-in-law who figures in the story.

R' Shmuel Strashun maintained a free loan fund which had set hours for the public. He would enter all the transactions in his account book, listing the name of the borrower, the amount he received, and the date that it was due. As soon as the borrower paid up, it would be entered next to his name and the debt cancelled.

A tailor once came to the RaSHaSH for a loan, to be payable within three months. On the day it was due, he came to settle the account, and laid the money on the table before the RaSHaSH. Being deeply engrossed in study, R' Shmuel's mind did not register the information.

"Leave it on the table," he said to him, with hardly a glance up.

The tailor left, assured that the matter would be duly registered. The RaSHaSH was involved in a difficult topic dealt with in the Rif. Having perused it at length, he shut the volume in order to put it away and look the matter up in another commentary.

But in the process, he laid the bills inside the sefer and absent-mindedly returned it to the shelf without having recorded the return of the loan.

Heaven willed it that he forget all about this transaction. We must say that this was ordained, since the RaSHaSH was very meticulous about his ledgers and always wrote everything down. It had never happened before — but forget he did.

A few days later, R' Shmuel leafed through his notebook to see who was behind in payment. He discovered that the tailor's debt was still outstanding. "Perhaps he is still hard pressed for the money," thought R' Shmuel. "I will let it ride for the meanwhile."

When another week passed and the tailor still had not come, R' Shmuel sent a message to him.

"What happened to the loan?" he asked the tailor, who had promptly appeared. "When you did not come on the appointed day, I decided to let it go for another week. But that time is up, now. I would like the money back."

The tailor stood there, dumbstruck. "But I paid you back! I paid you the entire sum on the due date, don't you remember?"

"If you had, I am sure I would have remembered. I would surely have written it down in my records, besides. But there is nothing written here. I am sorry, but I must have the money back."

The tailor was adamant. He insisted that he had already repaid his loan, but the RaSHaSH was equally firm in stating that he had never received the money.

With neither of them refusing to yield an inch, the matter had to be resolved, somehow. And so they went together to the beis din.

What could the judges do? It was a simple tailor's word against the RaSHaSH, whose reputation was impeccable. In the end, they ruled that the tailor must swear before the court that he had returned the money. The tailor was willing to do so, but the RaSHaSH, who was so completely convinced that he was right, trembled at the thought of letting someone swear falsely before the court.

"Never mind the money, then," said R' Shmuel. "I will not have a person swear falsely. I waive my claim."

"No," insisted the tailor, "I paid and I am ready to swear to it. I do not want the rabbi's favors; I want justice."

In the end, the tailor did not pay nor did he swear. The town was in an uproar.

Naturally, everyone sided with the rabbi, for who would dream of taking a tailor's word against such a great man as the RaSHaSH! That tailor, thought people, must not only be a liar, a thief and a scoundrel, but an arrogant fool!

People lost all faith in the tailor and no one came to him with their business. No one entered his shop all day and he was reduced to starvation. Left with no choice, he moved from the center of town to a suburb, where only gentiles lived. Here, he found enough business to keep him alive, but hardly more. He lived in extreme poverty.

A few years passed. One day, the RaSHaSH took down his copy of the Rif. As he opened it, an envelope fell out. It contained a sum of money. At that moment, it all flashed back; he recalled how he had been engrossed in study and for a fleeting moment, someone had entered and spoken to him, but the fact had not registered in his mind.

Who can describe his feelings of guilt at this realization! He was beside himself with grief. The tailor had been right, all along, he had paid back the loan. And he, R' Shmuel, had caused him to suffer so!

R' Shmuel did not hesitate a moment. He ran out and inquired where the tailor lived. He was told that he had moved away for lack of customers. The more he heard, the lower R' Shmuel's heart sank, for he realized that he was to blame for the tailor's ill fortune.

He inquired further until he succeeded in locating the tailor. He rushed into the shop and fell at the man's feet, weeping, "Gevald! Help me! I have sinned against you. Forgive me! You were right all the time. You did pay me back, only I forgot to record it! How can I ever right the injustice I did to you? You must forgive me."

"How can you make amends, rabbi?" asked the tailor bitterly. "You ruined my reputation and ruined my life. How can I forgive something so terrible as that? You virtually killed me! People went around calling me a liar, thief and scoundrel. No one would look me in the face. I became a pariah of society and was reduced to starvation. Do you think you can wipe the slate clean with just a few words? Do you know how much I suffered because of your oversight? How can I forgive you?"

The RaSHaSH was overcome by deep remorse. He sank into deep thought for a few moments, then turned to the tailor and said, "You are right. An apology is not enough for all the pain and damage I caused you. But I have an idea. I will visit every synagogue and beis medrash in the city and will declare before one and all that I have sinned. I will confess and tell them exactly what happened. I will clear your reputation once and for all."

The tailor shook his head. This would not make up for his years of suffering. "No, rabbi, I cannot forgive you. Do you know why? Because people will not believe it. They will still refuse to believe your word against mine, a rabbi against a simple tailor; they will say that you had pity on me because I lost all my business. But in their hearts, they will still think that I am a despicable fellow."

The RaSHaSH again sank deep in thought. The tailor was right. His confession would not be believed; it would be construed as a gesture of pity for the tailor. What could he do to really help the tailor? Finally, he hit upon a solution.

"Listen here. You have a son and I have a daughter. If I take your son for a son-in-law, no one will ever say anything against you again. They will believe that you spoke the truth and that you are a decent, honest man."

The tailor's eyes lit up. Yes, that would make the difference. "In that case, I forgive you," he said.

And so it came to pass that the RaSHaSH's daughter was married to the son of a simple, unlearned tailor. The tailor's reputation was redeemed and far more. People now gained a deep respect for him and he was reinstated in the favor of the community forever after.

What lesson are we to derive from this unusual tale? Whatever it teaches with regard to the importance of forgiveness, with regard to the marriage we see that Heaven had ordained this match according to the rule that "forty days before the forming of the fetus, a heavenly voice declares: the daughter of ploni [is destined] for ploni."

Heaven also decrees whether a person will be wise or stupid, but it cannot decree if he will be good or wicked. This is left up to a person's choice. Similarly, if he will be a Torah scholar or not. How was a match between a famous, distinguished rabbi and a simple tailor ever to come about? Under normal circumstances it would have been impossible. But Heaven had its intricate, unfathomable ways to bring two opposites together, as we have just witnessed.

End of Part 1